Recap:

The inspiration for this month’s American Dream series was a reader’s comment in the National Review:

[There is a] “lack of upward mobility in current American society. 40 or 50 years ago the expectation was, if you worked hard, went to college, paid your dues, you would be rewarded, advance and perhaps achieve a higher level of income and status than your parents. That whole dynamic has stalled, kids spend fortunes on educations which they cannot recoup, and the outlook for advancement has become grim, except for a chosen few. Anyone who has kids in their 20's and 30's should grasp this intuitively.”

Are these valid complaints? Specifically, is it true that:

There is little upward mobility in America.

It is unrealistic to expect hard work and a college education will eventually lead to higher income and status.

Doing better than one’s parents is an essential part of the American Dream.

Kids spend fortunes on educations which they cannot recoup.

The outlook for advancement has become grim, except for a chosen few

Part I of the series dealt with the history of the “American Dream”, a phrase coined by the freelance writer and historian James Truslow Adams around the beginning of the Great Depression. Parts II and III looked at different conceptions of the Dream as endorsed by respondents in various Gallup, Pew and NORC surveys. Responses ranged all over the place, from “freedom of choice in how to live one’s life” to “a good family life” to “the ability to retire comfortably”. Doing better than one’s parents (ie, intergenerational mobility) was not mentioned in any of the survey reports. Parts IV and V reviewed evidence on the benefits of a college education and whether upward mobility had stalled in America. It appears that most Americans move up the income ladder from young adulthood to middle-age, although some get stuck on the lower rungs (Chetty et al, 2017). A college education definitely helps, from a few classes to advanced degrees.

As for the expectation that “hard work” will eventually lead to good things, a few points: hard work alone does not lead to anything. Hard work alone does not guarantee a successful career. But I would wager that few people achieve career success without hard work being a factor.

Ok, I’m done with propositions 1, 2 and 3. Now I’m ready to tackle:

4. Kids spend fortunes on educations which they cannot recoup.

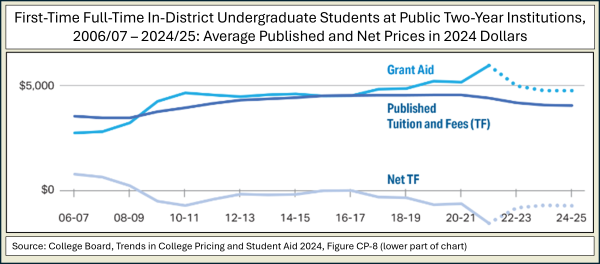

This is not true for public colleges, which are cheap. That’s because the vast majority of students do not pay the “sticker price” at these schools. In fact, according the the College Board, first-time full-time students at public two-year colleges have been receiving enough grant aid to cover their tuition and fees, on average, since 2009-10:

And the net tuition and fees for four-year public colleges have declined to an estimated $2,480 in the 2024-25 school year.

Of course, there are still school supplies and basic living expenses.

More from the Federal Reserve’s Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2024: Higher Education and Student Loans (published May 2025):

Most student loan borrowers with outstanding debt owed less than $25,000 on their loans.

— For comparison, the average new car loan is approximately $41,068 and the average used car loan is about $26,091 (Experian)

Borrowers with higher levels of education were more likely to carry higher balances of student loan debt.

— Individuals with higher education are also more likely to pay off loans, given their higher earnings.

Difficulties with student loan payments were greater for those who went to for-profit schools. .

— So if you’re worried about affordability, avoid for-profit schools.

Excluding people who have paid off their debt could overstate difficulties with repayment. At the time of the 2024 survey, among those who ever incurred debt for their education:

8 percent were behind on their payments

33 percent had outstanding debt and were current on their payments

59% had completely paid off their loans.

So, no, kids don’t have to pay a fortune to go to college. If they attend a for-profit private school, that’s their choice. Similar course offerings are generally available at public colleges. And while programs for advanced and professional degrees may be expensive, the eventual payoff can be quite high, especially in finance, medicine and law. Of course, there are people who struggle to pay off their student loans. But they’re the exception, not the rule.

References

The fading American dream: Trends in absolute income mobility since 1940. Chetty, Raj, David Grusky, Maximilian Hell, Nathaniel Hendren, Robert Manduca, and Jimmy Narang. Science 356, no. 6336 (2017): 398-406. https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.aal4617

Trends in College Pricing 2024 Report / College Board, October 2024 https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/Trends-College-Pricing-2024-presentation.pdf

Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2024: Higher Education and Student Loans / The Federal Reserve, May 2025 https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2025-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2024-higher-education-and-student-loans.htm

Previous Posts in this series:

Time to Rethink the American Dream, Part I: A Little History

Time to Rethink the American Dream, Part II: A Matter of Definition

Time to Rethink the American Dream, Part III: A Dream for Me But Not for Thee

Time to Rethink the American Dream, Part IV: Upward Mobility

Time to Rethink the American Dream, Part V: Good News and Bad News